Anxiety tends to stink, for the most part. There are times when being anxious can be useful, such as when you’re in fight-or-flight mode or when it keeps you alert to the needs of self-preservation. However, it can feel intrusive, interfering, and profoundly annoying.

Anxiety tends to stink, for the most part. There are times when being anxious can be useful, such as when you’re in fight-or-flight mode or when it keeps you alert to the needs of self-preservation. However, it can feel intrusive, interfering, and profoundly annoying.

The specific type of anxiety that I’m about to describe will sound very familiar. Everyone experiences some measure of stress when coping with the pressure to function and perform. For most people, while potent and experienced with great intensity, it generally eases after the trigger passes.

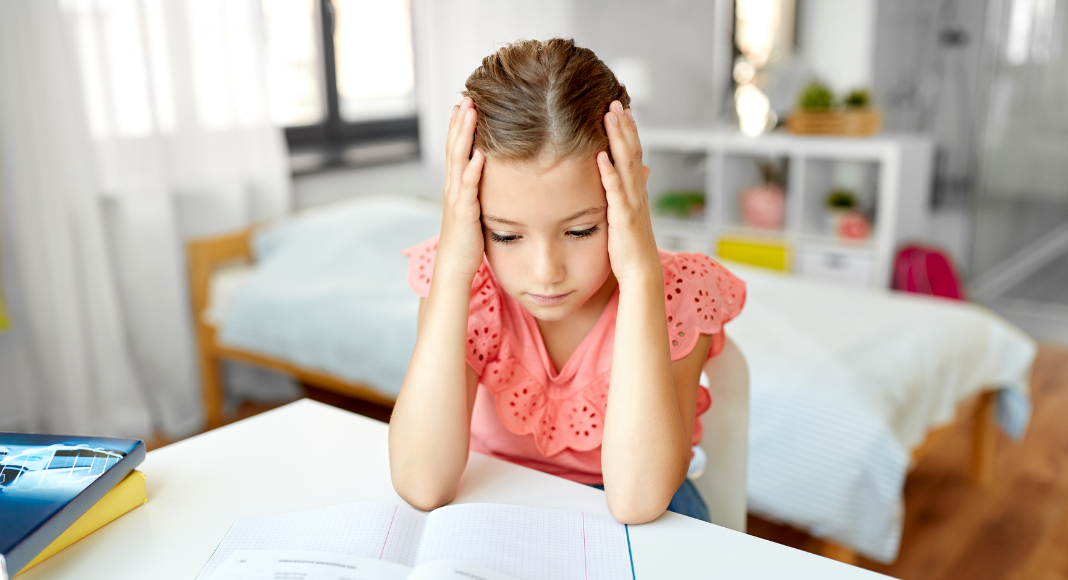

However, there are some for whom the anxiety does not pass, and it chips away at their ability to function in daily life. Cracks in the veneer can run the gamut from irritability to meltdowns to all-out tantrums. On the other end, it can also look like inactivity, decreased participation in social events, school or work refusal, the inability to leave one’s home, and a general loss of functional ability.

For parents, this can be a terrifying thing to witness, particularly when loss of function pairs itself with depression or a phobia. Watching a child disintegrate is painful and taps into deep-seated fears related to a parent’s regrets or disappointments about themselves.

Naturally, the instinct can be to try to resolve it as quickly as possible and freeze it in its tracks before it takes on a life of its own and causes the individual to hemorrhage motivation, self-esteem, and a sense of their capability.

It can become very tempting to ACT on behalf of the suffering person, resulting in impulsive choices. Sometimes parents try to explain the specific details of consequences or paint a picture of negative outcomes, all in the hopes of turning things around. Others might leap ahead to warn of the self-fulfilling nature of a bleak future and the many ways in which their child will not succeed if they keep doing A, B, and C. It is well-meaning, an attempt to save their child and inject some sense of the pitfalls of a situation, but is experienced as enormous PRESSURE.

The interesting thing about pressure though: pressure is seldom motivating.

If anything, it often has an opposite, paralyzing, almost chilling effect. Children often already know about the various negative outcomes associated with being non-functional. Most anxious children would give anything to magically change their fallibility because they don’t want to disappoint their families or seem somehow “less than” to society at large. They want so badly to be able to give their parents the ease of dreams and hopes fulfilled, but they just can’t. They’re not genies. They don’t have magic wands. They can’t make things happen on everyone else’s timeline. Believe me, if they could give that to you, they would. It would be a dream for them because people might finally stop PRESSURING them and ease off.

As counterintuitive as it might seem, the key to addressing anxiety is to ease up on the pressure and demands.

Children that are overwhelmed by a laundry list of ways in which they have yet to meet the standards of others run the risk of becoming tortuously uncertain and self-deprecating. Preventing all-out collapse requires the fully supported step of feeling like they actually can fall and still be loved. They need to communicate their thoughts and feel like their issues can be fully addressed without judgment.

The ability to do things in their own time and having the genuine approval of their parents to take alternative pathways to achieve a normative goal is crucial. Without anxiety being emotionally scaffolded and openly addressed, it can become a source of shame, devastatingly affecting a child. The good news is that children are pretty flexible and willing to adapt, even if things haven’t been said encouragingly in the past. Openly discussing and normalizing their struggles while being very mindful of the hidden ways that we can non-verbally communicate disapproval is an important step towards giving them the space they need to develop in their special way.